Like any art form, a book reveals plenty about its creator.

For example, Thomas Hardy was rather obsessed with farming being, like, the way of life.

Or, at least, that’s what reading Far From the Madding Crowd (1874) led me to assume. I could be wrong.

Something else I learnt was that, while it seemed that Mr Hardy was overcompensating whenever he launched into avid details of every square centimetre in a room, in actuality, he considered himself to be a bonafide, beret-wearing poet.

Think neon signs throughout the book, proclaiming, ‘I’m still a real writer, dammit, even if I’ve sold out to magazine serials.’

No clue how good he was at poetry, but he certainly had talent for describing characters, if not the setting. It boggled me why no one had told Mr Hardy that readers were fully capable of filling in any gaps left open by a book. Having to visualise the exact décor, layout, and atmosphere of a room before getting to the action or, rather, exposition, was considerably trying. And slow.

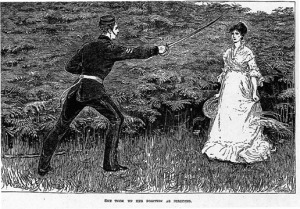

Mr Hardy wrote this neat little tale about Bathsheba Everdene – a terrible, terrible name – who fended off three suitors whilst inheriting the running of a farm. Being a product of my time, much like Mr Hardy was of his, I spent the majority of the book rolling my eyes at the typical, repressed fare that Victorians liked to serve up regularly (minus the cherries on top) about appropriate behaviour.

But then I thought – it was all a little too typical, wasn’t it?

You see, Mr Hardy, the sly old goat, smirked his way through the writing process. By creating a conventional story with characters behaving in proper ways, he managed to subversively cause his readers to question the logic behind social rules (particularly in regards to marriage). Though he explored such issues with more gutso in his later novels, Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure, Far From the Madding Crowd was certainly forward thinking.

Shame about the narrator’s Mr Hardy’s sexist comments on every second page.

True, they could be excused as standard for his day, but what made me laugh was that, it wasn’t women that our author had a problem with. Oh no, Mr Hardy seemed to have a personal issue with attractive women.

I guess it goes part and parcel with liking farming or whatever, but Mr Hardy strongly asserted that being pretty leads to all sorts of horrible things. Like vanity, and people living in cities, and dozens of men falling in love with one beautiful women, whilst all those poor, ugly, women that the love-struck men would have married were stuck with no prospects.

In fact, the narrator Mr Hardy made it very clear that Bathsheba should feel guilty for being so good-looking.

Methinks Mr Hardy was a tad bitter, yes?

(If you’re curious, Mr Hardy’s first marriage broke up because his wife lost her looks, leading him to seek out other companionship).

Like I said, it’s fascinating what one can deduce about the writer of a book, though it could feel like I’m prying a little too much. But sometimes I simply felt embarrassed on behalf of the author – *cough* Stephanie Myer *cough*.

Anyway, I had a less than stellar opinion of Far From the Madding Crowd – I picked it up because I was in the mood for an era piece, but didn’t want to subject myself to Jane Austen’s riveting gossip. It ended up being a soap opera love triangle quadrilateral that Austen would have been proud of. Except it was set on a farm.

Nevertheless, I found Mr Hardy to be far more compelling than his own characters, and I’m sort of looking forward to reading Tess of the d’Ubervilles and Jude the Obscure, if only to learn more about Mr Hardy’s motivations. And hopefully be in for further Zoolander references.

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

Pingback: 100 Books To Read … Or die trying | The Friande

The few poems I’ve read of Hardy’s have been really good, so maybe he was a poet first and a writer second? :) I haven’t checked out his fiction before but will wait to see what you think of his other works before I do. Great review!

He was definitely a poet first, and wrote novels to make money and gain publicity. That really comes across in the book, because he does great descriptions from a unique perspective, but cannot balance these out in proportion to the plot. I don’t think I’ll be reading his other books for a while, I’m thinking of something to cleanse my palate first :)

I hated Tess of the D’Urbervilles. I imagine you won’t like it.

Oh no, that really doesn’t sound promising :( Maybe I’ll put it off for a bit?

Interesting review, although I can’t agree with it as a big fan of Hardy. Yes I think Hardy was a poet first and foremost and I think that does come across in his novels. For me, his descriptions of the landscape etc are a major draw to his books, in some cases the landscape is almost a character in itself (e.g.Egdon Heath in Return of the Native), and he’s very much in the Romantic tradition of landscape reflecting mood etc. I don’t see him as being misogynistic either, merely portraying the lives of women in his society, (not forgetting that he was a market-driven author who did have to sell his books). He did write a lot of very strong female characters including Bathsheba, who does at least own her own farm even if she has rubbish taste in men :O). Some critics have tended to dwell on the ‘pessimism’ of Hardy, I rather think he was incredibly sensitive to the suffering of others, not just humans. I hope you enjoy Tess and Jude more than FFTMC, Jude is one of my favourites. It will be really interesting to see what you make of Sue Brideshead and Arabella.

I would disagree with Bathsheba being a strong woman because, while she did, at first, run her farm (& well), she came increasingly to rely on Oak. Particularly after she was married – she lost control of the farm – & when she was going to marry her next door neighbour, their farms were to be combined & looked after Oak on the neighbour’s direction. Moreover, she was about the only female character in the book – sure there was her maid, Fanny & those two old ladies making hay, who did very little, but everyone else was male & busy carrying the plot (with the majority of Bathsheba’s actions coming about as a result of someone else’s prodding).

I agree that he did write a market-driven book, but that doesn’t mean he needed to include as many misogynist comments as he did. Normally, I would have ignored these, as they were normal opinions for the times, but from someone who was chafing at social trends as much Hardy was, I would have expected more.

(Haha, if you didn’t notice I adore literary debate).

I suspect I enjoyed your review far more than I would enjoy this book … I tend to have such a problem with “the classics” because, as you pointed out, I’m a product of my age. (That being said, it is amazing I do something to antiquated as reading in the first place.)

I did read Jude The Obscure way way way back in the day … but it was forced reading and I never sought out old Mr. Hardy again.

And I agree — Bathsheba Everdene — is a terrible name!

I dread the day when (if) people stop reading. Our world would be much poorer. Or, at least, my personal world would be.

Bathsheba sounds like a bathing house for sheep. Ugh.

Thanks for commenting!

Well, I enjoyed reading your review of Hardy’s “Far From the Madding Crowd.” You are absolutely correct that Hardy considered himself a poet first, and fiction writer second (to pay the bills). He actually was a brilliant poet, and is now considered one of the great poets of the 20th century; and while paradoxical, is also considered to be one of the great fiction writers of the late-Victorian in the 19th century.

I really must disagree with you on the notion that he was a misogynist though. In fact, far from it. Hardy was a man who was profoundly troubled by the double-standards that were applied to women in his day. The plots of everyone of his books and short stories bear this out. Time and time again, Thomas Hardy utilized the powerful female characters of his novels to take issue with the Victorian cultural norms associated with sexism, education inequalities, and so forth. Bathsheba Everdene is just one example, a young (19 or 20 years old?) female landowner managing her own farm was indeed a rarety; and Bathsheba actually does quite well at it. She develops respect and trust from all her hired hands, and she ultimately ends up being respected by her peers (all of the other male landowners in the area). Does Bathsheba have terrible taste in men? Sure, but don’t we all struggle with that? It is part of Life, Love, and growing up.

Also, your statement, “If you’re curious, Mr Hardy’s first marriage broke up because his wife lost her looks, leading him to seek out other companionship.” is simply factually incorrect. Thomas Hardy’s first wife, Emma, died (probably heart disease) in their house at Max Gate in 1912. While they certainly had their ups and downs during the course of their marriage (and don’t we all), Hardy loved his wife very much and was actually quite devoted to her. There is simply no evidence whatsoever that he ever had an adulterous affair during their 38 year marriage. Hardy was known to develop ‘infatuations’ with various women during his marriage, and most of them ended up becoming long-time family friends of both Hardys (e.g., Florence Hennicker). Thomas Hardy married Florence Dugdale after Emma’s death. Ms. Dugdale had worked for both Hardys for several years as a sort of administrative assistant. Unfortunately, Emma Hardy was also probably suffering from some form of psychological breakdown, and became very mean-spirited and paranoid in the last few years of her life. This was a serious issue for all that encountered her.

I do hope that you will go back and read some more of Hardy’s amazing novels, short stories, and especially his poetry. Ultimately, I think you’ll find that this was an extraordinarily sensitive man who truly loved and genuinely cared for his female characters, as well as the lower class working women that he knew so well from his rural Dorset countryside. I strongly recommend that you read The Return of the Native, The Woodlanders, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, and his ‘magnum opus,’ Jude the Obscure. These are not trivial female characters in these novels–they are some of the most profoundly powerful women to be found in fiction. Cheers! Chris

Thanks for the comment.

Firstly, I am aware that he was troubled by the double-standards applied to women, as well as numerous other social constraints. This doesn’t mean, however, that he wasn’t a misogynist. The two aren’t mutually exclusive. And while I commend his efforts, they do not cancel out the numerous sexist comments scattered every few pages in Far From the Madding Crowd. I note that he didn’t generalise men down to their lowest common denominators at any point. Sure, Hardy could have been playing to the crowd when he published the book, but he could have just as easily left off with the remarks, and no one would have noticed – they add nothing to the story. I direct you to the reply (above) I made to a comment by Barbara, about why Bathsheba, to me, is not a strong woman (note that one can be intelligent without being strong).

Secondly, Hardy and Emma had been estranged for several years before she died; in fact, one of Hardy’s greatest regrets was not being able to say goodbye to her. When I said companionship, I referred to the flirtations Hardy had with other women. He may have slept with them, he may not have; it matters not. My sources indicated that Hardy’s infatuations with other women led to Emma’s psychological issues, after which she locked herself in the attic. These sources could be wrong, but I understood that Hardy was developing into quite the aesthete; and, while he was certainly devoted to his wife, Hardy’s later poems revealed that he missed their early marriage, when they were still attractive to each other.

I admit I didn’t research that thoroughly into Hardy’s life, rather relying on textual analysis of this book to draw my conclusions. But I’m of the opinion that a text reveals the unconscious thoughts and feelings of their author, as well as their ideological world view, far more so than a person’s letters etc. This is why I find Hardy, as a person, interesting – he was a modern thinker, and yet was so wrapped up within the beliefs of his time. Hardy was a paradox.

I’m definitely looking forward to reading his other works (I have a list of 100 Books I’m working through), simply because I’m curious. Thank you for the comment, and, trust me, I love a good literary debate!

I have to say that I am still troubled with your labeling Hardy as a misogynist; and while a “literary debate” can be interesting, and even fun on occasion, I will leave you with the statement that ‘I choose to respectfully disagree with you’ on that particular point.

I would urge you to read Rosemarie Morgan’s superb book, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy. Morgan teaches at Yale and is one of the preeminent Hardy scholars. I think Dr. Morgan can perhaps persuade you to change your mind about Hardy being a misogynist.

[Morgan, Rosemarie. Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy. London: Routledge, 1988 ISBN0-415-05850-3]

Agreeing to disagree sounds fine. I think I’ll wait to read Dr Morgan’s book until after I’d read Jude the Obscure and Tess of the d’Ubervilles, but thanks for the heads up!

I find that it is usually the authors that are more interesting to look into than the actual books they write! Farming? Misogynist? Each an extreme all its own! Hardy as a poet I will definitely have to look into for my review lists. I think after next week I will be caught up on my miscellany obligations. Misogynist? The last I heard of that word and term was in my criminality course. *shudder* I hated that class.

I was thinking about this the other day, & realised that the reason I like reading classic books is that I’m a history dork. I love reading about an author or a their time, & even if I disliked the book (like Oliver Twist), I’m still reasonably happy that I learnt something. Puzzles are also fun, which is probably why I like deciphering a text to figure out stuff about it’s writer.

I said misogynist because I didn’t want to use the word ‘sexist’. Why is there a term for sexism against women, but none for sexism against men?? Haha really glad I didn’t have to do criminality – congrats on getting through it!

That’s interesting that you didn’t like this! Yes, the mysoginist comments annoyed me, but after having read this just after reading Middlemarch, I appreciated Hardy’s story-telling abilities and, like you mentioned, his strength in developing his characters. I enjoyed, but did not love, this book.

Here’s my review — http://thebluebookcase.blogspot.com/2010/04/published-1874-its-about-story-of.html

I enjoyed this book at times, but at other times – particularly during his descriptions of the countryside – I had force myself not to skim through the paragraphs. Bad, Ilona!

Congratulations on finishing Middlemarch – I’m really glad it’s not on my list, because I don’t think I’m going to like it at all. Off to read your Far From the Madding Crowd review…

“Tess of the d’Ubervilles ” – I read this one and I saw a very good R.Polanski’s movie, based on the book. Perhaps Hardy was not a mysoginist but why oh why his heroine behaved the way she behaved (I don’t want to spoil anyone so I won’t elaborate – read the book) ? I think it was supposed to be one big fat warning – a beautiful woman is a handful and can be deadly!

Maybe he didn’t “hate” women, but he certainly saw them as the weaker sex. Which is kind of condescending: here, let me help you by speaking out against social customs because you certainly can’t help yourself. Oh and have a pat on the head too.

I have to read Tess of the d’Ubervilles as it’s on my list, but probably not for a while. I try to mix it up :)

Again, I must profoundly disagree. In no way shape or form did Hardy view women as “weaker sex.” In fact, quite the opposite. I strongly urge you to read more Hardy, as I believe that he, himself, will convince you that you are mistaken. One simply cannot simply classify the characters of Tess Durbeyfield, Eustacia Vye, or Sue Bridehead as representative of the “weaker sex.”

Frankly, I would like to resume this discussion after you’ve read some more of Hardy’s fiction. These are arguably some of the most stunningly amazing women of fiction.

Cheers!

Let me give you some reasons why I believe Hardy thought of women (at least at the time of writing Madding Crowd) as the weaker sex:

– The narrator’s (note: not the characters’) comments interspersed every few pages about how weak women are; not exactly the actions of a someone who was trying to further the woman’s cause. It would kind of be like me saying I support gay rights, yet writing a book with plenty of homophobic statements – it just doesn’t compute.

– Bathsheba’s every deed was ruled by fate – she was always reacting to her environment. Sure she was ballsy, but she quickly had to acquiesce to the wishes of the men in her life: Oak’s farming experience, Troy’s demands to do as her husband says, Boldwood’s marriage proposal which she has to accept including the fact that he would control her farm (which Oak was running by then anyway). Not to mention that the narrative punished her for her actions in regards to Troy, particularly as the ending (her marriage to Oak leading them both to be happy) was contrived.

– Nearing the end of the book, the text reinforces that rebellion will be stopped, sooner or later, for the community’s best interests. Pretty much every single action Bathsheba took that looked strong (turning down Oak & Boldwood’s marriage proposals because she didn’t want to be under the rule of her husband unless she loved him, and her running the farm for approx half the book) or an action that was typically female (her vanity, which is killed off at the end of the book) is classed as rebellion and, therefore, wrong.

You can campaign for animal rights, but you don’t have to think that every animal’s intelligence and disposition is on par with a human’s. So, sure, Mr Hardy was troubled by standards of his time, but that didn’t mean he believed women were the stronger sex (or equal to men in those arenas – though he wanted women to be treated the same as men and given equal rights). I don’t need to read the other books – they could be different or the same – but this one certainly is sexist. I’m not sure if you have studied literary criticism, but I’m of the mind that you analyse the text for your conclusions on the story, rather than the analysing the author. Yes, this book is sexist. Whether it was written that way consciously or unconsciously by Hardy doesn’t change that fact.