Like any art form, a book reveals plenty about its creator.

For example, Thomas Hardy was rather obsessed with farming being, like, the way of life.

Or, at least, that’s what reading Far From the Madding Crowd (1874) led me to assume. I could be wrong.

Something else I learnt was that, while it seemed that Mr Hardy was overcompensating whenever he launched into avid details of every square centimetre in a room, in actuality, he considered himself to be a bonafide, beret-wearing poet.

Think neon signs throughout the book, proclaiming, ‘I’m still a real writer, dammit, even if I’ve sold out to magazine serials.’

No clue how good he was at poetry, but he certainly had talent for describing characters, if not the setting. It boggled me why no one had told Mr Hardy that readers were fully capable of filling in any gaps left open by a book. Having to visualise the exact décor, layout, and atmosphere of a room before getting to the action or, rather, exposition, was considerably trying. And slow.

Thomas Hardy

Mr Hardy wrote this neat little tale about Bathsheba Everdene – a terrible, terrible name – who fended off three suitors whilst inheriting the running of a farm. Being a product of my time, much like Mr Hardy was of his, I spent the majority of the book rolling my eyes at the typical, repressed fare that Victorians liked to serve up regularly (minus the cherries on top) about appropriate behaviour.

But then I thought – it was all a little too typical, wasn’t it?

You see, Mr Hardy, the sly old goat, smirked his way through the writing process. By creating a conventional story with characters behaving in proper ways, he managed to subversively cause his readers to question the logic behind social rules (particularly in regards to marriage). Though he explored such issues with more gutso in his later novels, Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure, Far From the Madding Crowd was certainly forward thinking.

Shame about the narrator’s Mr Hardy’s sexist comments on every second page.

True, they could be excused as standard for his day, but what made me laugh was that, it wasn’t women that our author had a problem with. Oh no, Mr Hardy seemed to have a personal issue with attractive women.

I guess it goes part and parcel with liking farming or whatever, but Mr Hardy strongly asserted that being pretty leads to all sorts of horrible things. Like vanity, and people living in cities, and dozens of men falling in love with one beautiful women, whilst all those poor, ugly, women that the love-struck men would have married were stuck with no prospects.

In fact, the narrator Mr Hardy made it very clear that Bathsheba should feel guilty for being so good-looking.

Methinks Mr Hardy was a tad bitter, yes?

(If you’re curious, Mr Hardy’s first marriage broke up because his wife lost her looks, leading him to seek out other companionship).

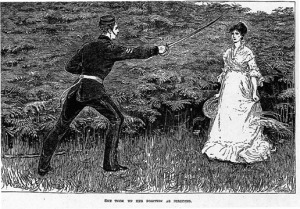

Original illustration of Sergeant Troy & Bathsheba

Like I said, it’s fascinating what one can deduce about the writer of a book, though it could feel like I’m prying a little too much. But sometimes I simply felt embarrassed on behalf of the author – *cough* Stephanie Myer *cough*.

Anyway, I had a less than stellar opinion of Far From the Madding Crowd – I picked it up because I was in the mood for an era piece, but didn’t want to subject myself to Jane Austen’s riveting gossip. It ended up being a soap opera love triangle quadrilateral that Austen would have been proud of. Except it was set on a farm.

Nevertheless, I found Mr Hardy to be far more compelling than his own characters, and I’m sort of looking forward to reading Tess of the d’Ubervilles and Jude the Obscure, if only to learn more about Mr Hardy’s motivations. And hopefully be in for further Zoolander references.

Stumble It!

Stumble It!